|

Yellow

FeverYellow

FeverYellow

Fever |

|

... the

Plague of Memphis |

| |

| |

|

During the 1800's Memphis was a very swampy area

and was well known as the filthiest and most foul smelling

city on earth. Open sewers contributed to the

unpleasant odor and they provided breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Because

it wasn't known at the time that mosquitoes spread disease, nothing

was done to improve the situation for almost 40 years.

In addition the sewer smell was enhanced by another

smell due to Memphis paving the streets with "Nicholson

Pavement" - which was wooden blocks impregnated with

creosote. These blocks had begun to decay

and send forth a poisonous smell. Plus the soil

all around was reeking with

the excrements of ten thousand families. And the

city had

no organized service to carry garbage away. It was

one filthy city with a terrible smell - and the perfect

breeding ground for

YELLOW FEVER.

|

|

|

| |

|

Yellow Fever originally hit the United States in 1668-69

in the New York-Philadelphia area. It didn't

make its way south until 1828, when it first appeared in

New Orleans. Within days, it moved up-river and found

the perfect breeding ground - swampy and filthy Memphis.

During it's first epidemic in 1828, there

were 650 cases and 150 deaths. Consider that the

population was under 1,000 at that time and you get an

idea of how deadly this disease was. |

| |

| |

Memphis had six

major Yellow Fever epidemics

|

1828 |

First Yellow Fever

epidemic |

650 Cases |

150 Deaths |

| |

|

|

|

|

1855 |

Second Yellow

Fever epidemic |

1250 Cases |

220 Deaths |

| |

|

|

|

|

1867

|

Third Yellow Fever

epidemic |

2500 Cases |

550 Deaths |

| |

|

|

|

|

1873 |

Fourth Yellow

Fever epidemic |

5000 Cases |

2000 Deaths |

| |

|

|

|

|

1878 |

Fifth Yellow Fever

epidemic |

17000 Cases |

5000 + Deaths |

| |

|

|

|

|

1879 |

Sixth Yellow Fever

epidemic |

2000 Cases |

600 Deaths |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on small photos to

enlarge them. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yellow

Fever had originally come from West Africa and may have been

brought to the United States on Slave Ships. The disease

requires warm weather to survive and thrives in wet and hot

summers where mosquitoes can breed prodigiously. There

seemed to be no rhyme or reason to who fell ill. Once

infected the victim developed a piercing headache, then a

chill, and then a temperature. The pain could be so

intense that victims sometimes became demonic and ran through

the streets screaming and thrashing. Internal bleeding

would develop which produced the trademark black vomit,

composed of blood and stomach acids. The liver and

kidneys failed and the victim turned yellow and soon died,

usually within 2 weeks. Some who survived had bodies and

minds permanently crippled. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nuns

care for the ill |

Nuns care for the ill |

The dead and the dying... |

Pick up the dead... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Memphis

had been exposed to Yellow Fever in 1828, 1855, and 1867 and each

time it was brought north by steamer from New Orleans.

In 1867 it was quite severe although it was confined to the section

of the city where it had developed. But nothing prepared the

city for the devastation the fever brought in the 1870s. In

August of 1873 it came again. Two boats had arrived from New

Orleans, each with a sick man on board. These men were put off

at a low, marshy area known as "Happy Hollow" not far from the Navy

Yard. One died before he could be taken to the hospital and

the other shortly after reaching it. The attending physicians

suspected Yellow Fever, but kept it to themselves. Suddenly

several deaths on Promenade Street were announced and it was now

official. The authorities tried to cleanse and disinfect the

city, but it was too late. The deaths grew daily. Tens

of thousands of people fled. The streets were deserted except

for the funeral trains. Catholic and Protestant clergymen and

physicians ran untold risks, and men and women freely gave their

lives in the service of others. 2500 people died between

August and November. As usual, the first frost ended the

plague, but they didn't know why. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Doctor Calls |

Nun Calls |

Harpers |

Welcome Frost... |

Internment Camp |

|

|

|

|

|

<

And the onslaught of Yellow Fever didn't prevent

Memphis from holding its 1873 annual carnival with the

gorgeous pageants. At the time, the 2500 deaths

constituted the most Yellow Fever victims in an inland city -

ever. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Great Yellow Fever Epidemic of

1878

Yellow

Fever returned to Memphis with a vengeance in 1878. There had been a mild

winter, a long spring, and a torrid summer. By July New

Orleans had reported an epidemic of the fever. Memphis immediately threw up

checkpoints at major points of entry into the city. 25,000 Memphians fled the city, and of those left, 17,000 caught the

fever and 5,150 of those died.

|

|

| |

25,000

Evacuate |

|

|

|

|

In 1878 William Warren, a deckhand,

entered Memphis from President's Island. Two days later

he was dead. Several days later, New Orleans verified

that Yellow Fever was present, and Warren had come from that

city. Those who could afford to leave the city immediately

left. In July the city had a population of 47,000. Over

25,000 evacuated. Quarantine facilities were set up in

Germantown and the main facility on President's Island.

Passenger ships were blocked from the harbor. Schools were

converted to hospitals. Refugee Camps were set up. Of

the 19,000 people who remained in Memphis, 17,000 contracted Yellow Fever.

Of the 41 police officers, only 7 were fit for duty. One by

one, they fell, dying at their posts. Food and fuel became

scarce. Americans from other parts of the country came through with money and

provisions which arrived on steamboats and long trains filled with

supplies. |

|

|

Quarantine Station |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The only people who went out were the collectors of the dead. With horse and wagon,

they shouted "Bring out your dead!" And then they loaded

and took all to the cemetery for a hasty burial. They believed

that corpses spread the disease so they tried to get them

in the ground as quickly as possible. They also thought

the disease was spread by bad air. So with temperatures

close to 100, they boarded up their windows and kept

fires burning to ward off the outside air. When people

died, their clothing and beds were dragged into the streets

and burned. Names of

the dead were written in ink in leather-bound ledgers.

There was an average of 200 deaths per day and corpses were

everywhere. Half of those who died were the Irish.

Sixteen Catholic priests and 30 sisters died in their heroic

battle to tend the sick.

|

|

Pick up the dead ... |

Quick burials |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pick up the dead |

Camp Williams |

Memphis Police 1878 |

St. Mary's School becomes

Hospital |

Distribution of Food |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Board of Health on River |

Camp on the Bluffs |

Disinfectant Wagons |

Examine travelers credentials

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Half a million dollars which had been contributed by other states was

expended in the burial of the Memphis dead and for the needed medical

attention during the reign of the plague. By the time

this major epidemic ended, Memphis had lost a total of over

30,000 people to Yellow Fever and the city was financially

broke and desperate. In 1879, the state

legislature revoked Memphis' city charter.

|

|

Collecting Contributions |

Collecting Contributions |

|

|

|

|

|

And once again, the onslaught of Yellow Fever didn't prevent

Memphis from holding its 1878 annual carnival with the

gorgeous pageants. At the time, the 5000 deaths

constituted the most Yellow Fever victims in an inland city -

ever.

=> |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There was

a positive effect of the 1878 epidemic: It was the

first time in Memphis history that the black community

served as patrolmen on the police force. Long

thought to be immune to the disease, blacks contracted the fever in

large numbers in 1878 - but only 7% died. Although not

proved, it's now felt that repeated exposure to Yellow Fever over

many generations in West Africa provided many blacks with a higher

resistance to the disease. The African Americans who remained

in Memphis during the epidemics worked tirelessly with the

sick and dying as nurses, cart drivers, coffin makers, and

grave diggers.

They

continued to hold positions in Memphis police, fire, and

other departments long after blacks were barred from

such employment elsewhere. However, by the

end of the century, Memphis joined other southern cities

in denying city employment to the people who had helped

carry them through the devastating epidemic.

|

|

|

Memphis

Police 1890 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some Heroes and

Martrys of the

Yellow Fever Epidemics |

|

|

|

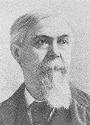

J. M.

Keating

stayed in Memphis during the worst outbreak in 1878. He

was publisher of The Memphis Appeal and wrote a first person

experience of the disease.

Mattie

Stephenson

came from Illinois to Memphis as a nurse during the epidemic

of 1873. The "Heroine of Memphis" died shortly after she

began ministering to the sick and dying. |

|

|

| |

J. M. Keating |

Mattie Stephenson |

|

| |

|

|

Sister

Constance

of St. Mary's Episcopal Cathedral stayed in Memphis during one

outbreak, going from house to house to care for the sick.

Sometimes she found abandoned children amid the rotting corpses of

their parents. She contracted the disease and died a few days

later.

Click here for excerpt from her

diary.

Sisters

Thecla, Ruth, Frances

- St. Mary's Episcopal nuns who stayed in the city to care for the

ill. The are all memorialized on the high altar at St. Mary's

Cathedral.

|

|

|

| |

Sister Constance |

1879 Book

|

| |

|

Charles Carroll Parsons

was

a priest from St. Mary's

Episcopal Church who died caring for Yellow Fever victims.

Louis Landford Schuyler

was a priest from St. Mary's Episcopal Church who died caring

for Yellow Fever victims. |

|

|

| |

Charles Carroll Parsons |

Louis Schuyler |

|

| |

|

The Howard

Association

was

originally created in New Orleans

specifically for the Yellow Fever epidemics to arrange for

volunteer professional nurses

and doctors to care for the poor who had contracted the

disease, and to help pick up the bodies.

Butler P.

Anderson,

president of the Howard Association in 1878 was one of the

first to die after contracting the fever in Grenada, Mississippi where he

had gone to nurse the sick. His wife also died shortly after

returning from his burial.

|

|

|

| |

Howard

Association |

Butler Anderson

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dr.John Erskin

was a member of the Howard Association. He was one of

the 110 doctors who tended the sick and dying in 1878.

And he was one of the 33 doctors who died from the disease.

Rabbi Max Samfield

was a member of the Howard Association. He remained in

the city throughout the 1873 and 1878 epidemics and

administered to the sick and buried the dead of all races and

religions. |

|

|

| |

John Erskin |

Max Samfield |

|

|

|

|

Dr

R. H. Tate

-

recruited by the Howard Association, the first African

American to practice in Memphis. While helping with the

1878 epidemic he contracted the disease and died within three

weeks.

Annie

Cook

was a Memphis Madam who stayed in the city during the

Yellow Fever epidemic, turned her brothel into a hospital and

took care of the sick. She became known as "Mary

Magdalene of Memphis" after she succumbed to the disease. |

|

|

| |

R. H. Tate |

Annie Cook |

|

|

|

|

Dr. William Armstrong made house calls

around the clock to care for

the ill during the 1873 Yellow Fever epidemic and again during

the 1878 epidemic until he contracted the virus and died.

Father Joseph Kelly

of St. Peter's Parish became known as "Father of the

Orphans" and "selfless caregiver among victims of Yellow Fever

epidemics". During the 1873-1878 epidemics, he evacuated

all the orphans. |

|

|

| |

Dr. Will Armstrong |

Fr. Joseph Kelly |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yellow Fever Burials:

During the outbreaks of Yellow Fever there were over 5,000

fatalities in the city. Some 2500 of the Memphis victims are buried

in four public lots at Elmwood; among them are doctors, ministers,

nuns, and even prostitutes who died tending to the sick. The four mass

burial areas are referred to as "No Man's Land". There is a plaque

identifying the area.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No Man's Land |

Madam Sutton |

Mattie Stephenson |

St. Mary's Nuns |

Parsons |

Schuyler |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eugene Magevny |

Jeff Davis, Jr |

Mrs. Butler Anderson |

McKiven and the Poor |

Howard Association Memorial

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Memphis Cleans

Up... |

|

|

|

A major

positive side effect came about after the 1879 epidemic, as

Memphis leaders embarked on ambitious sanitation reform.

Strict sanitation laws were finally passed outlawing open

privies. Regular trash collection was instituted, in

addition to clearing away all the garbage that had accumulated

since the 1878 epidemic due to lack of funds to remove it.

The decaying wooden paving blocks were torn up and gravel

mixed with limestone roads were laid. The centerpiece of

the sanitary reforms was a revolutionary sewer system designed

by George Waring of New York. He used an unprecedented design which

separated the sanitary sewer system from the storm sewers.

It was the design that made Memphis the envy of others and was

to revolutionize the design of sewer systems across the

nation. Ironically George Waring died in 1898, after

returning from Cuba where he was modernizing their sewer

system. The cause of death: Yellow Fever. |

|

|

|

|

George

Waring |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Almost a

decade after the 1878 epidemic, an artesian aquifer was

discovered under Memphis, which would provide the city with an

abundant supply of clean and safe water. This became one

of the best water sources in the country.

All these reforms and changes immediately benefited the business district and the wealthier

neighborhoods of the city. It would be years before these

innovations would reach the neighborhoods of the poor. The city

simply had no funds.

|

|

|

|

Artesian Pump Station |

|

|

|

|

The

rebirth of Memphis was described by Professor Gerald M. Capers of

Tulane University: "There have been two cities on the fourth

Chickasaw Bluff: the old river town existing prior to 1878,

and the new city that has grown up since 1880".

Some 22 years before Dr. Walter Reed identified the mosquito as the

carrier of yellow fever, Memphis had been transformed to a new

and vibrant city. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Yellow Fever is

transmitted by the bite of an infected Mosquito..." |

|

|

|

|

Dr. Carlos Findlay,

Cuban doctor, first proposed in 1880 that mosquitoes might

carry the Yellow Fever virus. This, of course was met

with much skepticism.

Walter Reed,

U.S. Army pathologist and bacteriologist would later lead the experiments that

proved Yellow Fever is transmitted by the bite of an infected mosquito.

The Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C. is named in his honor.

During most of the 19th century it was widely believed that Yellow

Fever was spread by articles of bedding and clothing of the

victims. In 1900 a small camp was established and controlled

experiments were performed on volunteers. Reed proved that an

attack of Yellow Fever was caused by the bite of an infected

mosquito and that a house became infected only by the presence of

these infected mosquitoes and not by clothing and/or bedding. |

|

Carolos Findlay |

Walter Reed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symptoms |

Studies |

Yellow Fever |

Sulphur Fumigator |

Posters |

Habits |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

City Beautiful

Campaign's

|

|

|

|

<

Memphis created the "Clean Up, Paint Up, Fix Up" campaign in 1941.

The program went National.

Memphis has been a five-time winner of the Nation's

Cleanest City award, from 1948 - 1952, and again in 1983.

It was the "cleanest Tennessee city" from 1940 to 1946.

> |

|

|

Clean up ! Paint up !

Fix up ! |

|

City Beautiful Marker |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Martyr's Park |

|

|

|

|

|

|

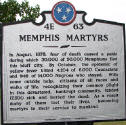

Located on a bluff near the Memphis bridge, Martyr's Park opened

in 1972. It's dedicated to those who did not flee from

the yellow fever epidemic in 1878, who stayed to help those

who were infected, and to bury the dead. Almost 80

percent of those who stayed caught the fever and one-quarter

of them perished. The centerpiece of the park is the sculpture

by Harris Sorrelle. |

|

Sorrelle

Sculpture |

Marker |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today,

Yellow Fever has not been eradicated but it has been greatly

reduced by routine childhood vaccinations in endemic

countries. Cases in the U. S. are now very rare.

A Harvard scientist,

Max Thieler

developed the most effective vaccine against Yellow fever.

It immunized U. S. soldiers during World War I and became the

world standard. This achievement won him the Nobel Prize

in Medicine in 1951. |

|

| |

Max Thieler |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Credits |

|

|

The

Historic-Memphis website does not intentionally post copyrighted

photos and material without permission or credit.

On

occasion a "non-credited" photo might possibly be posted because we

were unable to find a name to give credit. Because of the nature of

our non-commercial, non-profit, educational website, we strongly

believe that these photos would be considered "Fair Use. We have

certainly made no monetary gain, although those using this website

for historic or Genealogy research have certainly profited. If by

chance,

we have posted your copyrighted photo, please contact us, and we'll

remove it immediately, or we'll add your credit if that's your

choice. In the past, we have found that many photographers

volunteer to have their works included on these pages and we'll

also do that if you contact us with a photo that fits a particular

page.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The "Historic-Memphis" website would like to acknowledge and thank the

following for their contributions which helped make this website

possible: Memphis

Public Library, Memphis University Library, Memphis Law Library,

Memphis Commercial Appeal, Memphis Press Scimitar, Shelby County

Register of Deeds, Memphis City Schools, Memphis Business Men's

Club, Memphis Chamber of Commerce, Memphis City Park Commission,

Memphis Film Commision, Carnival Memphis, Memphis Historical

Railroad Page, Memphis Heritage Inc, Beale Street Historic District,

Cobblestone Historic District, Memphis Historic Districts, Vance

Lauderdale Family Archives, Tennessee State Archives, Library of

Congress, Kemmons Wilson Family, Richard S. Brashier, Lee Askew,

George Whitworth, Woody Savage and many individuals whose assistance is

acknowledged on the pages of their contributions. Special

thanks to Memphis Realtor, Joe Spake, for giving us carte blanche

access to his outstanding collection of contemporary Memphis photos.

We do not have high definition copies of the photos on these

pages. If anyone wishes to secure high definition photos,

you'll have to contact the photographer or the collector.

(To avoid any possibility of contributing to SPAM, we do not

maintain a file of email addresses for anyone who contacts us). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|