|

Memphis and

The Civil War |

|

...in

Vintage Drawings and Photos |

|

|

|

Initially, most Tennesseans showed little enthusiasm for

breaking away from the nation. In 1860, they had

voted by a slim margin for the Unionist John Bell, a

native son and moderate who continued to search for a

way out of the crisis. In 1861, 54 percent of the

state's voters voted against sending delegates to a

secession convention, defeating the proposal for a State

Convention. If it had been held, it would have

been very heavily pro-Union. But with the attack

on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, and Lincoln's call for

75,000 volunteers to put the seceded states back into

line, public sentiment turned dramatically against the

Union. |

|

|

|

| |

|

In

a June 8, 1861 referendum, East Tennessee held firm against

separation, while West Tennessee returned an equally heavy

majority in favor. The deciding vote came in Middle

Tennessee, which went from 51 percent against in February to 88

percent in favor in June. Having ratified by popular vote

its connection with the Confederacy, Tennessee became the last

state to formally declare its withdrawal from the Union. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the small photos to see an

enlargement. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the

1860s, Memphis was a lively and thriving, riverboat town with

more than its share of bordellos and saloons. There was a

Main Street and a Beale Avenue.

Along

Main Street, one could find all types of shops and businesses,

as well as numerous hotels, restaurants, and theatres.

Riverboats loaded with cotton lined the riverbank and nearly

400,000 bales a year were being sold in Memphis. The city

was on its way to becoming the largest cotton market of the

world. |

|

Memphis

Landing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Memphis Bluff 1864

|

Memphis Landing 1864 |

Main Street 1860s |

Beale 1860s |

|

|

|

|

In

1862, Memphis serves briefly as the State Capitol when Nashville

fell to the Union in March of that year. All the

state records were stored in the Masonic Temple at Madison and

2nd.

=>

After

the war, the Tennessee Governor convened the state legislature

from this building. |

|

|

|

|

Masonic

Temple |

Marker |

|

| |

| |

|

The Battle of

Memphis ... |

| |

|

This

naval battle was fought on the Mississippi River below the city on

June 6, 1862. The result was a crushing defeat for the Rebels

and marked the virtual eradication of a Confederate naval presence

on the river. In spite of the lopsided outcome, the Union Army

failed to grasp its strategic significance. It's primary

historical importance is that it was the last time civilians with no

prior military experience were permitted to command ships in combat.

The battle remains as a demonstration of the ill effects of poor

command structure. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Battle of Memphis |

Battle of Memphis |

USS Essex |

Battle of Memphis |

|

|

|

|

Union

officer Charles H. Davis moved down the Mississippi with a squadron

of ironclad gunboats. Accompanying him were six rams commanded

by Colonel Charles Ellet. The Confederate fleet, commanded by

James E. Montgomery, a riverboat captain with no military

experience, was going to move south to Vicksburg, but was

notified that there wasn't enough coal in the city to fuel his ships

for the voyage. While Montgomery technically commanded the

fleet, each ship was run by it's own civilian captain, who was empowered to

act independently once they left port. Compounding that

was the fast that the gun crews were provided by the army and served

under their own officers. But Montgomery's group decided to stand

and fight. |

| |

C. H.

Davis |

As the

Union fleet approached Memphis, Davis ordered his

gunboats to form a line of battle across the river, with the

rams in the rear. They opened fire on Montgomery's

lightly armed rams. They closed in and the battle

engaged at close quarters deteriorating into a wild melee.

They succeeded in sinking all but one of Montgomery's ships.

With the fleet eliminated, Davis approached the city and

demanded its surrender. Union casualties were limited to

one, while Confederate casualties are not known but most

likely they were between 180 and 200. The destruction of

the Confederate fleet eliminated any Confederate naval

presence on the Mississippi. |

Chas Ellet

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Battle of Memphis |

Battle of Memphis |

Battle of Memphis |

Battle of Memphis |

|

|

|

|

<=

Thousands

of Memphians watched the battle from the bluffs above the

Mississippi in an

area that would later be named "Confederate Park" . The

battle for Memphis lasted all of 90 minutes.

|

|

Thousands

watch from this Bluff

|

|

|

| |

|

|

<=

After the battle, Union soldiers marched to the Post Office

and lowered the Confederate flag on the roof, replacing it

with the U. S. flag. Confederate sympathizers closed a

trap door which locked the soldiers on the roof. The Union Commander

threatened to shell the city if the city didn't surrender.

The soldiers were allowed to descend and within hours Memphis

was occupied and for the remainder of the Civil War, it would be an occupied

city.

The

occupation probably saved it from destruction, because the last few cities the Yankees had captured they burned to

the ground. |

|

Union Flag

flies over Post Office |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Occupied

Memphis ... |

|

|

|

|

|

Ulysses S. Grant was ordered to Memphis to become district

commander of the Union

Forces. At the

beginning of the Memphis occupation, he made his headquarters

at the Hunt-Phelan home on

Beale Avenue, where he set up a tent on the lawn. The home's

library was used as his office but he slept in the tent as a bond with his men.

However, he soon moved to plush quarters at the nearby Hotel Gayoso,

where he also had the comfort of being joined by his wife

Julia and their children. |

|

| Ulysses

Grant |

|

Julia

Grant-children |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photos of Ulysses S. Grant taken

in Memphis |

Hotel Gayoso |

Hunt-Phelan Home |

Hunt-Phelan Library |

|

| |

|

Grant arrived in Memphis June 23, and found the city in

“bad order, with secessionists governing much in their

own way.” He wrote, “In a few days I expect to have

everything in good order.” This included posting picket guards around

Memphis, ordering clergymen to omit prayers for the

Confederacy, and a provost marshal, backed up by three

regiments, is directed to keep order in the city. Grant

also orders his Union occupiers to behave themselves.

Wandering about, pilfering, or straggling are forbidden,

and the soldiers are told to stay in their camps.

Three

articles appearing in the Daily Appeal describe

incidents in the city shortly after the Battle of

Memphis. One of them refers to General

Grant

=> |

|

| |

Daily Appeal

1862 |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

During occupation, Memphis becomes a center for troop disbursements and a

major shipping

center for supplies.

The

Hunt Phelan house serves as a hospital and lodge for wounded

Union soldiers. After the war a Freedman’s Bureau school

was established at the home. |

|

Soldiers

Hunt-Phelan 1863 |

|

|

|

|

|

Davies Manor Plantation: Located just north of the stage

route between Memphis and Nashville, This was a popular stop for

soldiers from both sides. The plantation managed to operate

throughout the war despite many family members joining the

Confederate army. |

|

Davies Manor

Plantation |

|

|

| |

|

|

FORT PICKERING:

Confederate authorities had originally established Fort Pickering in 1861,

building on the site of a frontier-era fort.

Union commanders took over and imposed martial law and posted garrison forces.

At first it was generally a lenient occupation, in the hope of winning over secessionist citizens, who

comprised the great majority in Memphis. But finding that

these secessionists remained hostile and defiant, the authorities

adopted an increasingly harsh policy. This included the

seizure and destruction of private property, the imprisonment or

banishment of those who refused to take an oath of allegiance to the

Union, and the forcible emancipation of slaves.

|

|

|

|

Fort Pickering |

|

|

| |

|

Ulysses

Grant appointed

General William T. Sherman as Commander of the Third Division

of the Army of Tennessee. Sherman ordered Fort Pickering expanded after

the Union takeover in 1862 and the site became one of the great

supply and staging areas in the West. Hundreds of slaves,

escaping from surrounding states, found work here. Camps provided

housing, churches and schools for the men. Later, some of the

ex-slaves manned the fort’s guns as U.S. soldiers. This was a

rough point for white Memphians. During his period in Memphis,

Sherman had very little to do, so he spent the time planning his "March to the Sea". |

|

|

|

William T.

Sherman |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sherman and

Officers |

Sherman's Tower |

Colored Regiment 1864 |

Sherman's Memphis Map |

Marker |

|

| |

| |

|

Generals Hurlbut and

Washburn:

Major General S. A. Hurlbut took command of Memphis after

Grant and Sherman. Like them he keep a tight clamp on

the city. Yet he continued their policy of allowing open

trade on the Mississippi and a local government as long as the

voters signed a loyalty oath. He tells Grant he has it

"under control, but is short of troops to stop the smuggling"

and asks to stay in charge. His successor is Major

General C. C. Washburn. He clamps down harder and closes

the open trade policy and suspends the city government.

Washburn remained in control until the war ended. |

|

|

| |

Gen

Hurlbut |

Gen

Washburn |

|

| |

|

*

Fort Pickering has its

own comprehensive coverage on another page of this website >

Click here |

| |

|

Resistance,

Smuggling,

and

Spying... |

| |

|

For most Tennesseans, Union occupation was a devastating

experience. Many left the city and became refugees

for the duration of the war. Those who stayed faced the

agonizing decision of whether, and/or how to resist the enemy.

The great majority did resist to some degree. The

boldest went beyond defiant to engage in active resistance,

smuggling and spying. Memphians found themselves

directly under the enemy's thumb and subject to constant

scrutiny. But there were also many advantages.

Army authorities provided police and fire protection, health

services, and courts of law. They doled out free

provisions to the needy and permitted the operation of

schools, churches, and markets. The Military Government

tried to get all Memphians to sign an "Oath to the United

States"

= > |

|

|

| |

|

In

1863, the Memphis Chamber of Commerce sent Abraham Lincoln this

interesting letter asking that occupied Memphis should be

treated like a "loyal city". |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

Military occupation lasted more than three years and affected

Memphians attitudes more than the war itself. Although they

lived a relatively normal life during this period, Memphians hated

occupation rule and the city became a focus for illicit trade in raw

cotton, which was in great demand by northern cotton mills.

This trade in illicit cotton also corrupted the Union Army officers.

Union Army officials refer to Memphis as "Gomorrah of the West".

Yet they legalize and regulate prostitution during their

occupation - not that Memphis needed any help along these lines.

=> |

|

|

|

<=

DAILY

APPEAL-

This is an artist rendering of what was the Memphis Daily

Appeal office in 1862. The retreat of the newspaper began June

6, 1862 when the printing equipment was loaded on a railroad

flat car hours before Federal gunboats smashed the Confederate

fleet and captured Memphis. Over the next three years, the

newspaper published in Grenada, Jackson and Meridian in

Mississippi, Atlanta, Georgia and Montgomery, Alabama until

April 6, 1865, when Federal troops destroyed the type at

temporary offices in Columbus, Georgia. Fortunately, the

press had already been smuggled out of town and

hauled from it's hiding place in Macon, GA to

Chattanooga, |

|

where it was loaded aboard a steamer bound for Cairo, Ill. The

newspaper resumed Memphis publication at No. 13 Madison Avenue

on Nov. 5, 1865.

|

| |

|

1862 - Hauling

sugar and cotton

from their hiding places for

shipment north. The City Ice House (left) was damaged by a

shell during the battle between Union and Confederate

gunboats in the harbor that preceded the city's capture

=> |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Burning Cotton |

Ginny

Moon-Spy |

Lotte

Moon-Spy |

Ginny Moon |

Belle Edmondson-Spy |

Isabella

Edmondson |

|

|

|

|

|

Many Women actually served as

soldiers in the army by disguising themselves as men.

One famous example is Cuban born Loreta Velazquez who became a

soldier and spy known as Harry T. Buford. She switched

back and forth from espionage and fighting in major battles to

traveling between New Orleans, Memphis, Richmond, collecting

information. |

|

Harry T. Buford -

Loreta Velazquez |

"Harry" in

Memphis Bar |

|

|

| |

| |

|

IRVING

BLOCK PRISON:

During the Civil War, this row of office buildings on Second Street,

opposite the northeast corner of Court Square had been a Confederate

hospital. After the fall of Memphis in 1862, the Union Army turned

it into a Civil War Prison to house Confederate sympathizers.

As a prison, conditions became so deplorable that even the prison

commandant was dismissed in 1864, but he was re-instated at the

request of General Grant. The prison had become known as "the

filthiest place ever occupied by human beings". It was so notorious

that it was eventually closed by order of President Lincoln himself

in 1865. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Irving Block Prison |

The building 1907 |

Marker |

Two ladies to prison |

Restitution to Heirs |

|

| |

|

*

Irving Block Prison had

its own comprehensive coverage on another page of this website >

Click here |

| |

| |

|

HOSPITALS:

Being an occupied city earned Memphis its status as a major medical center

in the Mid-South. Wounded prisoners came by boat and wagon to

be treated at hospitals that began to specialize as the war

progressed. Prior to the war the city had one hospital.

By the end of the war, there were 15.

The Union used the hotels and warehouses of Memphis as a “hospital

town” with over 5,000 wounded Union troops being brought for

recovery. The Civil War was one of the "bloodiest" in history

- with over 620,000 casualties. The overwhelming operation

performed in hospitals was amputations.

|

|

|

"Bloody" war |

|

| |

|

The new Overton Hotel at Main and Poplar was used as a hospital.

This

Hotel had not yet opened when the Civil War began. During the war

both sides used the building as a hospital and as quarters. After

the war ended, it officially opened as a hotel in 1866.

The Woolen

Building in Howard's Row is among the oldest buildings in Memphis

and was an early cotton trading center. In the 1850s it also housed

the large slave market of Isaac Bolton. It also served

as a hospital during the Civil War. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overton

"Hospital" |

1861 Article |

1863 Article |

1865 envelope

- Overton Hosp. |

1865 Letter from Overton Hospital |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Woolen Bldg today |

Woolen Plaque |

Vintage Woolen photo |

|

Woolen Bldg today |

|

| |

|

A section

of the Gayoso Hotel was also used as an army Hospital, designed for

the reception of wounded patients only.

Female nurses

"prepared food, stocked shelves, and made the wounded as comfortable

as possible." The Gayoso team was led by Mother Mary Ann

Bickerdyke, perhaps the most famous nurse of the Civil War.

She became well known for her ability to bypass bureaucracy.

And she was the only woman ever allowed in Sherman's camps. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

The army hospitals in Memphis

were the Gayoso, the Adams, the Washington, the Webster, the

Jackson, the Union, the Jefferson, the Marine Hospital, and a small

Officer’s Hospital on Front Street. Two hospitals were set

aside for contagious diseases—the Smallpox Hospital, which was

located in the enlarge state-owned Memphis Hospital, and the Measles

Hospital, located in the First Baptist church. Later in July

1863, the First Baptist was reorganized as the Gangrene Hospital.

Successful experiments in the use of the bromine treatment of

gangrene were carried out there, which greatly reduced the mortality

of that dreaded wound complication. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

*

Letters

from a Union Soldier to his wife: Thomas

Hannah, Jr., Illinois 95th Infantry, Company G, was stationed at

Adams General Hospital, Number 3, in Memphis from 26 January 1863 to

30 July 1864, serving as Ward Master. During this period he

wrote over 100 letters to his wife Elizabeth Marshall Hannah in

Belvidere, Illinois. He discusses life in Memphis and

speaks about the nurses with whom he worked.

Michael

Bryan Fiske, great, great grandson of Thomas Hannah, Jr. has

transcribed these letters and shared some of them with us. They are

all courtesy of the Family of Robert Huntoon Hannah, grandson of

Thomas Hannah, Jr. We think you'll agree that these letters

are unique. To visit a separate in-depth page on Thomas Hannah Jr..

with more letters ...

Click here. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Union Casualties from

the siege of Vicksburg were evacuated mainly by hospital boat up the

river to Memphis. Later the same hospital boats were used to

transport patients from Memphis to St. Louis and on to Cairo.

Two of the more famous hospital ships were the City of Memphis

and the Red Rover, |

| |

|

|

|

|

| City of

Memphis |

Red Rover |

Red Rover

Ward |

Reinforcements for Grant's army |

|

| |

| |

|

The 2nd Battle of

Memphis...

Major

General Nathan Bedford Forrest became obsessed with freeing

prisoners from Irving Block Prison, and it was upper most in his

mind when he made a daring raid on the Union-held city in 1864. His

raid had three objectives: to capture three Union generals posted in

the city; to release Southern prisoners from Irving Block Prison;

and to cause the recall of Union forces from Northern Mississippi.

He struck early in the morning but didn't find the generals at Hotel

Gayoso,

although one, Major General Washburn made his escape to Fort

Pickering in his night shirt. Union troops were also able to prevent

the attack on Irving Block Prison. Although the raid had failed in

two of Forrest's objectives, he was successful in influencing Union

forces to return to Memphis from northern Mississippi, which did

provide the city more protection. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forrest` |

Hotel Gayoso |

Irving Block Prison |

Washburn Escapes |

|

| |

| |

|

Battle of Fort

Pillow AKA

known as Massacre of Fort Pillow

Fort Pillow was located 40 miles north of Memphis and this famous

battle was fought April 12, 1864. The battle ended with a

massacre of surrendered Federal troops by soldiers under the command

of Confederate Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest. |

| |

|

The fort had been a Confederate fort, but the rebels had

evacuated in order to avoid being cut off from the rest of the

Confederate army. Union forces took over and used the

fort to protect the river approach to Memphis. On this

date Forrest and his troops attached the fort with

considerable power, followed by frequent demands for

surrender. Union Major Booth refused to surrender.

After another attach, Major Booth was killed and the

Confederates swarmed over the fort. Up to that time few

Union men had been killed, but immediately upon re-claiming

the fort, the confederates seemed intent on indiscriminate

butchery of the whites and blacks, including the wounded.

They were bayoneted, shot, or sabred - men, women, and

children. The dead and wounded were piled in heaps and burned.

Out of the garrison of 600, only 200 remained alive. 300

of those massacred were negroes.

Union survivors claimed that the Confederates indiscriminately

killed Union troops, even as they tried to surrender.

Forrest and his officers stoutly denied that a massacre had

occurred and offered their own explanations of why so few

Union soldiers survived. A commission made up of North

and South was appointed to investigate. Both sides

concluded that there had been a massacre. Most

historians accept this verdict. What makes the issue so

controversial is that so many of the Union dead were African

Americans. |

|

|

Harpers Weekly 1864 |

|

|

|

Leslie's Weekly 1864 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Burying the dead ... |

|

|

|

The Union held Memphis for the remainder of the war, taking

advantage of its transportation links and founding several hospitals

in the city to care for up to 5,000 wounded troops from across the

region. Many of these large concentration of injured troops

died while in Memphis, creating the need for a cemetery. A

site, 32 acres in northeast Memphis was selected, and in 1867, the

first burials were made. While originally called Mississippi River

National Cemetery, the name was shortened to "National Cemetery" in

1869. |

|

Memphis National Cemetery |

|

|

|

|

|

Over

1,000 Confederate soldiers and veterans are buried in

Confederate Soldiers Rest, in Elmwood Cemetery. Many other

Confederates are buried elsewhere in the cemetery. The first

burial was in 1861 and the final internment was in 1940. Union

soldiers were also buried here in the 1860s but almost all were

removed in 1868 and re-interred in Memphis National Cemetery.

Two Union generals remain at Elmwood.

There are 20

Confederate generals buried here. |

|

| |

Elmwood Cemetery Confederate

section |

|

|

|

|

The Sultana

Riverboat Explosion of 1865 occurred when the ship's boilers

exploded and the ship sank near Memphis. It was the greatest maritime disaster

in U. S. History. 1,800 were killed, most of them Union

soldiers returning home after the end of the Civil War. Many of the victims

were originally buried at Elmwood

Cemetery. When National Cemetery opened in 1868, these

soldiers were re-interred there. Unfortunately their

wooden caskets were marked with chalk and that identification

was lost due to a rain in route to the cemetery. Thus

Memphis National Cemetery has the second largest population of

Unknown Soldiers in America. |

Sultana before explosion |

Sultana Marker |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Confederate Burials |

|

|

|

|

UCV |

|

Confederate soldiers couldn't be

buried in National Cemeteries, and they, nor their widows, were

eligible for benefits from the U.S. Government.

The

United Confederate Veterans was founded in 1889 to help as

a "benevolent, historical, social and literary Association".

Their primary functions were to provide for widows and orphans

of Confederate soldiers, preserve relics and mementos, care for

disabled soldiers, preserve records of service and to organize

reunions and gatherings where funds could be raised to support

their work. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reconstruction

... |

|

|

|

President Johnson wanted to restore the Union in as little time as

possible. While Congress was in recess, the president began

implementing his plans, which became known as Presidential

Reconstruction.

His plan offered general amnesty to all who would take an oath of

future loyalty.

Johnson

returned confiscated property to white southerners, issued hundreds

of pardons to former Confederate officers and government officials,

and undermined the Freedmen’s Bureau by ordering it to return all

confiscated lands to white landowners. Johnson also appointed

governors to supervise the drafting of new state constitutions and

agreed to readmit each state provided it ratified the Thirteenth

Amendment, which abolished slavery. Hoping that Reconstruction would

be complete by the time Congress reconvened a few months later, he

declared Reconstruction over at the end of

1865. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Andrew Johnson |

Reconstruction |

Idealic version of

Emancipation |

Inciting Riot? |

No Confederate Money... |

|

|

|

|

To coordinate efforts to protect the rights of former slaves and

provide them with education and medical care, Congress creates the

Freedman's Bureau. One of the bureau's most important functions was

to oversee labor contracts between ex-slaves and employers. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The sudden emancipation of thousands of slaves, without property,

education and means of economic support, could have created a

demoralized class and led to total chaos and famine. The actual evidence

suggests a smoother transition than one might have expected. But it

was a lot for the Southerner to comprehend right after losing

a war for "The Cause..." and the transition certainly was far

from perfect ... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Amnesty Oath |

Carpetbaggers |

Emmancipation Proc. |

Education |

15th Amendment |

First Vote |

|

|

|

|

There was a strange "twist" at the end of the war in Memphis.

The city had escaped the destruction of so many other Southern

cities and it had a booming economy. When Lincoln signed the

Emancipation Proclamation which freed all slaves within

"Confederate-held territory" and allowed African Americans to serve

in the Federal army, Memphis was occupied by Union forces and no

longer a Confederate city. Ironically at war's end, slavery

continued unabated, not only in Memphis but in all of Tennessee, as

well. Congress quickly passed the thirteenth amendment and

Tennessee adopted the measure in December of 1865 - thus Slavery

ended in Tennessee. |

|

|

|

The

conflict between the races didn't end. Confederate

soldiers came home to a transformed society that gave as much

legal protection to a black laborer as it did to a white

planter. Many of the returning vets found this

intolerable and immediately set about to change things; if not

to the way they were before the war, then to something

similar. There were white-led race riots in Memphis, New

Orleans, and a host of other Southern towns between 1874 and

1876, where whites finally restored their control over the

cities. Thus, while the Civil War changed the legal status of

race in America, it didn't change people's hearts. |

|

| |

KKK in

Memphis |

|

|

|

|

The Race Riots

of 1866... |

| |

|

During the War, Memphis became a haven for

freed slaves seeking protection from their former owners. The

black population increased from 3,000 in 1860 to 20,000 in 1865.

Racial tensions were heightened when black Union Army soldiers were

used to patrol the city. A riot was sparked on May 1, 1866,

when the horse-drawn hacks of a black man and a white man collided.

As a group of black veterans tried to intervene to stop the arrest

of the black man, a crowd of whites gathered at the scene. Fighting

broke out, and then escalated into three days of racially motivated

violence, primarily pitting the police against black residents. When it was over, 46

blacks and two whites had been killed, five black women raped, and

hundreds of black homes, schools, and churches had been vandalized

or destroyed by arson. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Harpers 1866 |

The Riots |

Burning Black Schools |

|

Riot Marker |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The official report:

Through

early 1866, there were numerous instances of threats and fighting

between black soldiers and white Memphis policemen, who were mostly

(90%) Irish immigrants. Officials of the Freedmen's Bureau reported

that police arrested black soldiers for the minor offenses and

treated them with brutality. Although black soldiers were

commended for restraint, rumors spread among the white community

that blacks were planning some type of organized revenge. Trouble

was anticipated when most black Union troops were mustered out of

the army on April 30, 1866. The former black soldiers remained in

the city while awaiting discharge pay.

On the afternoon of May 1, the chronic hatred

between the city police and the now discharged black soldiers

erupted into armed conflict. Details of the specific incident that

initiated the conflict vary. The most widely held account is that

policemen were attempting to take into custody several ex-soldiers

for disorderly conduct and were resisted by a crowd of their

comrades. Some historians attribute the inciting incident to the

collision between two carriages of a black man and a white man.

After a group of black veterans tried to intervene to stop the

arrest of the black man, a crowd of whites gathered at the scene,

and fighting broke out. In each incident there was

confrontation between white police officers and black Union Army

soldiers. There also appeared to have been multiple confrontations

followed by waves of reinforcements on both sides, extending over

several hours. This initial conflict resulted in injuries to several

people and one policeman's death, possibly self-inflicted due to the

mishandling of his own gun.

The initial skirmish ended after dusk and the

veterans returned to Fort Pickering, on the south boundary of

downtown Memphis. Having learned of the trouble, attending officers

disarmed the men and confined them to the base. The ex-soldiers did

not contribute significantly to the events that followed.

The subsequent phase of the riots was fueled

by rumors that there was an armed rebellion of Memphis' black

residents.[5]

These false claims were spread by local officials and rabble

rousers. Matters were made worse by the suspicious absence of

Memphis Mayor John Park and the indecisive commitment of the

commander of federal troops in Memphis, General George Stoneman.

When white mobs gathered at the scene of the initial skirmish and

found no one to confront, they proceeded into nearby freedmen's

settlements and attacked the residents as well as missionaries who

worked there as teachers. The conflict continued from the

night of May 1 to the afternoon of May 3, when General Stoneman

declared martial law and order was restored.

No criminal proceedings were held for the

instigators or perpetrators of atrocities committed during the

Memphis Riots. The United States Attorney General, James Speed,

ruled that judicial actions associated with the riots fell under

state jurisdiction. However, state and local officials

refused to take action, and no grand jury was ever invoked. Although

criticized for his inaction, General Stoneman was investigated by a

congressional committee and was exonerated. The Memphis Riots did not mar his political

career as he was later elected governor of California (1883–87). |

|

|

|

Tennessee was the first of the seceding

states readmitted to the Union on July 24, 1866. Because

Tennessee had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, it was also the

only one of the secessionist states that didn't have a military

governor during the

Reconstruction

period. |

|

|

|

|

|

Post Reconstruction

... |

|

|

|

After the formal end of Reconstruction, the struggle over power in

Southern society continued. For generations white Tennesseans had

been raised to believe that slavery was justified. Some could

not accept that former slaves were now equal under the law.

With violence and intimidation against freedmen and their allies,

White Democrats regained political power in Tennessee and other

states across the South in the late 1870s and 1880s. Over the next

decade, the state legislature passed increasingly restrictive laws

involving African Americans. In 1889 the General Assembly passed

four laws described as electoral reform, with the effect

of essentially disfranchising most African Americans, as well as

many poor Whites. Legislation included implementation of a poll tax,

timing of registration, and recording requirements. Tens of

thousands of taxpaying citizens were without representation well into the 20th century. |

|

|

|

The Jim Crow laws and "separate but equal" restrictive laws will

continue as a way of life for decades in the South, and to some

degree in other parts of the country. Racial segregation

will "officially" end with the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

|

|

|

| |

Colored Only Fountains |

Colored Waiting Rooms |

|

|

|

|

|

Confederate President Jefferson Davis was imprisoned for 2 years

and then the treason charges were dropped. He had no

money, property or income. Finally he is offered a job as

President of the Carolina Insurance Company in Memphis. He

and his family move to the city and live here from 1869- 1873.

His daughter is married in the house on Court. A young son

dies in one of the Yellow Fever epidemics and is buried at

Elmwood Cemetery. The Insurance Company goes bankrupt and

the family relocates to Biloxi, Mississippi where he dies in

1889. |

| Jefferson

Davis |

Memphis Home |

|

|

|

|

|

Confederate Park was dedicated in 1908 and planned as a Memorial

to the Civil War. It was part of the great designer George Kessler's

"Grand Design" for Memphis. During the War, the Mississippi

River below this park was the sight of an intense battle between

the Union and Confederate forces. Many lives were lost and

they are remembered at Confederate Park. Today, the park

provides a great perspective where the battle occurred and there

are markers to read first-hand accounts of the battle.

|

|

|

| |

Davis Statue |

Confederate

Park |

|

|

|

|

Forrest Park was established in the early 1900s and was another

of George Kessler's "Grand Designs for Memphis" parks. The

sculpture of Forrest is by Charles H. Niehaus, whose work can

also be seen at the Library of Congress. His sculpture is

considered one of the finest equestrian public park statures in

the U.S. It took him 3 years to model and nearly nine months for

the casting. It's 21' 6" high. The cost of $32,359.53 was raised

by private organizations. The bodies of Forrest and his wife

were re-interred from the Forrest family plot at Elmwood Cemetery to

Forrest Park in 1904. |

|

Forrest Park - Statue |

|

|

|

*

Forrest Park and the

story of the statue are thoroughly covered on another page of this

website >

Click here |

|

|

|

When

Riverside Drive was constructed in the mid-1930s, Jefferson

Davis Park was built on what had been an old dumping ground for

construction debris and dredge materials from the Mississippi

River. It was enlarged to its present size in 1937, using more

material dredged from the river. The Park was named after

Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy, who lived in

Memphis from 1869 to 1873 and who was president of an insurance

company here. |

|

Jefferson Davis

Park |

|

|

|

|

|

United

Confederate Veterans Reunions ... 1901, 1909, 1924

Memphis is

the only city to host three of the United Confederate Veterans

Reunions - which brought millions of dollars into the city. In

1901, the Reunion was considered so important to the city that an

astonishing $80,000 was raised to construct an 18,000 seat

Confederate Hall on the site of Confederate Park - the building to

be demolished at the end of the 3 day reunion. One of the

largest single donations of $1,000 came from the first black

millionaire Robert Reed Church. That first reunion in 1901 drew 125,000

visitors to the city. That's a lot of money. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1901 Front St |

1909 Bijou Theatre |

1909 Grand Parade |

1909 Grand Parade |

1924 Parade |

|

|

|

|

*

The UCV Reunions have

their own comprehensive coverage on another page of this website

>

Click here |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2013 Updates ... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Confederate Park |

Forrest Park |

Jefferson Davis Park

|

|

|

|

|

In

February 2013, without public notice, the Memphis City Council dropped all three names

of these parks and removed the

names from the signs at the parks because it said the names "evoked

a racist past and were unwelcoming in a city where most of the

population is black". As yet they have not come

up with "acceptable" alternate names for the three parks, but Confederate Park

may become "Memphis Park" or "Promenade Park".

Forrest Park may be named "Health Sciences Park" or "Civil War

Memorial Park" and Jefferson Davis Park may become "Mississippi

River Park" or "Harbor Park". There is

also a movement to rename one of the parks after civil rights activist

Ida B. Wells, and Mayor Wharton wanted to name one of them after

Maxine Smith, who fought for decades to have the graves and the

statue removed from Forrest Park. The outcome of the park

statues has not been decided. If past history is any

indication, the statues will be removed, placed in storage... and

quietly forgotten.

Update 2017:

In December the Memphis City Government quietly changed some laws

giving the city permission to sell Forrest Park (Health Sciences

Park) to a non profit company for $1000. The non-profit had

been created for this purpose and as soon as the bill of sale was

signed, large cranes went into action and removed the Forrest statue

and moved it to an unknown location. They also sold

Confederate Park (Memphis Park) and removed the statue of Davis.

Historic-Memphis website note:

FACT: There was an American Civil War. It was all about

slavery. Changing some names of Memphis Parks won't change

that. No matter what new name is applied to these parks,

there will always be a footnote about the original names that stood

for over a hundred years.

Renaming these

parks will not erase the South's greatest shame.

What the city council has done with this 2013 ruling creates an even

greater divide in Memphis racial relations.

As offensive as some find Confederate symbols, those symbols

represent Memphis history. That history should not be denied. It

is part of the South's good, bad and ugly, as well as the nation as

a whole.

To change names that are historically relevant is an attempt to

change the course of history. For a city government to attempt

to bury the past by pretending it didn’t exist is a major exploitation of power. Will the burning of history books be

next on their agenda? |

|

|

|

<><><><><> |

|

|

|

It's rare to find a large southern city that was virtually untouched

by the destruction of the Civil War. Memphis is one of those

rare cities. It should be the major treasure-trove of great

early southern architecture in America. Yet, virtually no

buildings from before the Civil War remain in the city.

Memphis continues to have this tendency to erase it's history or

not to come to terms with its historic identity. |

|

|

|

|

Masonic Temple

. Madison and 2nd

The building, dating from 1850, was demolished in the 1950s. |

| |

|

|

|

Hotel Gayoso . Main Street

This building burned in 1899. A grander Gayoso replaced it

in 1902, but never quite achieved its former glory. That

building still exists and has now been restored for use as

apartments, restaurants, and offices. |

| |

|

|

|

Hunt-Phelan Home . Beale Street

The building from 1828 still exists. Almost all the land has been

divided and the home itself is now on the "endangered list". |

| |

|

|

|

Davies Manor Plantation . Bartlett

The home from 1807 still exists. It's built as a

'log and chink' house made of squared white oak logs. The

name comes from Logan Davies who acquired the building in 1851.

He and his brother eventually added 2000 acres and put the land

to use as a plantation. |

| |

|

|

|

Fort Pickering

. on the Bluffs

The fort was demolished in 1866. Not one trace of it exists on the bluffs above the Mississippi. |

| |

|

|

|

Irving

Blum Prison . 2nd - at Court Square.

The buildings were demolished

in 1937 |

| |

|

|

|

Woolen Building . Union Avenue

This building still exists in the section known as "Howard's

Row" on Union Avenue.. |

| |

|

|

|

Overland Hotel - Main and Poplar

The Overland was sold to the city in 1874 and then used as a

court house until 1919. It was demolished in 1920 so Ellis

Auditorium could be built on the site. |

| |

|

|

|

Bijou Theatre -

Main and

Linden, Approximately where the Chisca Hotel is located.

The Bijou Theatre was as large as the Orpheum. It

burned in 1911 and was not rebuilt. |

| |

|

|

|

Jefferson Davis Home - 129 Court

This building was demolished

in the 1930s |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Civil War Memorabilia ... |

|

|

|

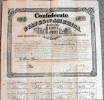

Confederate Coins, Bonds, and Currency...

It's worth more now than when it was in circulation

(It

was almost worthless when it was in circulation).

Be careful because the market is overrun with counterfeit

Confederate money. |

|

|

|

| |

Very Rare Coinsq |

Confederate Bonds |

Bonds |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 CSA Dollars |

100 CSA Dollars |

500 CSA Dollars |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Canon |

Bugle |

Drum |

Uniform |

1861 |

TN War Vets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1864

Freedman's Documents |

1863

Telegraph |

1862 Order |

1863

Letter: Lady to Husband |

1864 Ordnance

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Credits |

|

|

|

The

Historic-Memphis website does not intentionally post copyrighted

photos and material without permission or credit.

On

occasion a "non-credited" photo might possibly be posted because we

were unable to find a name to give credit. Because of the nature of

our non-commercial, non-profit, educational website, we strongly

believe that these photos would be considered "Fair Use. We have

certainly made no monetary gain, although those using this website

for historic or Genealogy research have certainly profited. If by

chance,

we have posted your copyrighted photo, please contact us, and we'll

remove it immediately, or we'll add your credit if that's your

choice. In the past, we have found that many photographers

volunteer to have their works included on these pages and we'll

also do that if you contact us with a photo that fits a particular

page. |

|

|

|

The "Historic-Memphis" website would like to acknowledge and thank the

following for their contributions which helped make this website

possible:

Memphis

Public Library, Memphis University Library, Memphis Law Library,

Memphis Commercial Appeal, Memphis Press Scimitar, Shelby County

Register of Deeds, Memphis City Schools, Memphis Business Men's

Club, Memphis Chamber of Commerce, Memphis City Park Commission,

Memphis Film Commision, Carnival Memphis, Memphis Historical

Railroad Page, Memphis Heritage Inc, Beale Street Historic District,

Cobblestone Historic District, Memphis Historic Districts, Vance

Lauderdale Family Archives, Tennessee State Archives, Library of

Congress, Kemmons Wilson Family, Richard S. Brashier, Lee Askew,

George Whitworth, Woody Savage and many individuals whose assistance is

acknowledged on the pages of their contributions. Special

thanks to Memphis Realtor, Joe Spake, for giving us carte blanche

access to his outstanding collection of contemporary Memphis photos.

We do not have high definition copies of the photos on these

pages. If anyone wishes to secure high definition photos,

you'll have to contact the photographer or the collector.

(To avoid any possibility of contributing to SPAM, we do not

maintain a file of email addresses for anyone who contacts us). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<><><><><> |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|